| Once you have selected that exceptional company name that projects your new venture, there are at least three different processes to undertake in order to truly secure that name and have it become a brand. If you only get one of those three name rights, you may not be able to garner all of the brand recognition your enterprise needs, and you may be competing with other businesses for claims to that outstanding name. |

The 3 Steps:

- Own the trademark to that name.

- Register an internet domain name version of your company’s name.

- Secure the name as an entity name in the state where your entity is formed.

A trademark is a word (Oracle®), phrase (Just Do It ®), symbol (such as Apple's partially-eaten Macintosh) or design (such as The Gap's blue and white "GAP" icon), or a combination of any of those, that identifies the source of a product or service. In the U.S., unlike in most other countries, you can have an unregistered (common law) trademark, but we’ll only talk about registered trademarks so you can secure the broadest rights for your mark.

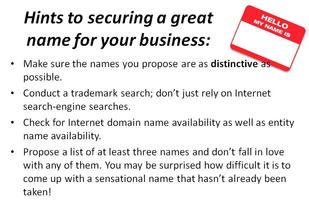

Generally, in order to claim a trademark in the U.S. you must be the first user of that name in commerce or you must have filed a federal trademark registration with the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (“PTO”) prior to that first use (known as an “intent to use” application.) (See http://www.uspto.gov/trademarks/process/file/addreq.jsp). How do you know if you are the first to use a particular trademark? Unfortunately, simply performing an Internet search won’t do. A trademark attorney can help you obtain a trademark availability search that will identify any similar marks used in your category of product. Note that categories of products for trademark purposes are published by the World Intellectual Property Organization (“WIPO”) and may not necessarily be intuitive to interpret. A trademark search will help you determine whether the name you selected would likely cause confusion about the source of the product, i.e., would the name of the product likely cause a potential customer to associate your product with another company?

Once an application is submitted, the PTO will assess the likelihood of customer confusion, as well as the strength of the trademark (its distinctiveness) since generic terms cannot be registered as trademarks. If there are no objections by the PTO, or you overcome its objections, your trademark will be published in the PTO’s Official Gazette. Anyone who believes that your published trademark should not be granted registration because it infringes its own mark or is generic can file an official opposition to your mark, which begins a process that is similar to a trial. If there are no objections, your mark will be registered (or in the case of an Intent to Use application where you have not yet used the trademark in commerce, you will have six months to do so before you can claim a registered trademark).

Also note that in order to protect your trademark outside of the U.S., you need to register your trademark, for the most part, in each individual country where you seek trademark rights.

Most companies register a “second level domain” name (the name before the .com, .org, .biz, etc.) that contains their trademarked entity name or trademarked product name. You may register a second level domain name with registrars (companies that are in the business of selling domain names), such as GoDaddy and Network Solutions. Generally, if a second level domain name is not already taken by another user, it will be awarded to the applicant. Note that there is no procedure in the application process for automatically checking to see whether an applicant’s selected domain name will infringe the trademark rights of someone else. Disputes over domain names based on trademark rights can be adjudicated in federal courts or under ICANN’s (Internet Corporation for Assigned Names and Numbers) Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy.

Unlike federal trademark rights and Internet domain names, the names of corporations and limited liability companies (LLCs) are granted by the states in which they are organized. So when filing your company’s charter document with the secretary of state of the state in which you would like your corporation or LLC to be formed, your charter will be accepted if the name you have selected is distinguishable from other names on record with the secretary of state.

Moreover, unlike the PTO's examination of trademark categories, states do not distinguish entity names based on the products or services they sell or the industries in which they participate. For example, while the trademark “Zirienko” can be registered for use by a bakery as well as for use by a location-based software application company, there cannot be both Zirienko, LLC (the bakery) and a Zirienko, Inc. (the software application company) registered in Delaware. In addition, if your entity “does business” in a state other than the one in which it was formed (and the definition of “doing business” is defined by each state), you may also have to clear the company’s name in that other state as well.

While there is no requirement to have your brand name be the same as the name of your corporation, most technology companies tend to use their corporate names as their most recognized brand names. One clear exception is the entity known as Research in Motion Limited, the company that develops and markets the BlackBerry® line of smart phones. Although Research in Motion® is also a registered trademark, that company’s main brand is its BlackBerry® line of smart phones. There also may be the occasion where you can secure both the trademark rights and the domain name for the brand you would like to have associated with your company, but that name is already registered with the secretary of state so it cannot become your corporation’s name. In such a case, you can select a different corporate name, but have your brand name become a “dba” (doing business as, also known as a “fictitious business name”) filed in the county in which your business is headquartered

With contributions from Aylin Demirci.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed